“Building a church is a bit like rebuilding a religion and restoring its essence.” So said Gio Ponti on the subject of religious architecture, of which the Concattedrale at Taranto is among the most significant examples in contemporary Italy.

How was Mimmo Jodice able to confront a building of this kind? Back in 1974 he had published a book entitled The Devout, and he has always had an eye for manifestations of popular religiousness. He has long been inspired, too, by masterpieces of a different religiousness, of the kind that produced the sculptures and buildings of the classical Mediterranean world. He is, moreover, a photographer who has not represented human figures (at least not living ones) since the 1980s. He has concentrated instead on landscape and architecture, or on what might perhaps better be described as places.

But he has never confined himself to what is still, all things considered, such a clearly defined genre as that of architectural photography.

To cut a long story short, he is a photographer who transforms into presences, or figures if you like, the very elements of landscape. He has built his philosophy on the relationship between the flagrancy of real facts and intellectual influences.

As Jodice himself has written: “I believe we Italians live in a country where reality and history have such an overwhelming presence and character that photographers cannot but be moved by them (…) But it is always the real thing, the actual scenery, that prevails. I believe the choice, made by the Italian group that caused this way of photographing to emerge, is the most correct, the closest to the essence of photography.”

That is the point, the meeting-point between Gio Ponti’s buildings – real and ideal – and Mimmo Jodice’s photography: a quest for the essence of action and language.

Combined with a deep awareness of the peculiarity of Italian culture, it is always and in any case a quest driven by this urge to compare with the past, even when constructing, photographing, and imagining the present and the future. To photograph a church, therefore, and a contemporary one in this case, is for Jodice not so much to reconstruct religion as to reconstruct once again his own approach to photography.

It is an attempt to bring it back to its most authentic, and at the same time to render the essence of what is photographed.

These images dedicated to the Concattedrale at Taranto are in fact a summing-up, as it were, of Jodice’s most distinctive approach to interiors, to things as such, and to the relationship established between themselves and the spectator.

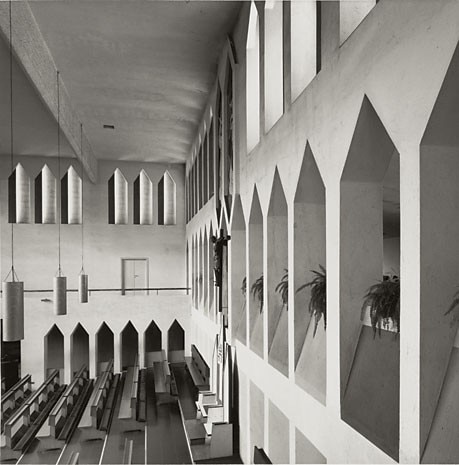

The photographer does not seek to represent the building, but rather to interpret it, while treating the repetition of forms as the fulcrum of his own vision and of Ponti’s oeuvre. The motif of the geometrical figure returns constantly from exterior to interior, connecting every element of the composition. But it also ends up, particularly in the pews, as the character that has always been present, through its absence, in the artist’s photographic world.

It is no longer only the structural element, no longer only a decorative element: it is something more. It is the essence of the place, the icon through which reality is transformed, through which the metamorphosis from inanimate object to character occurs – without questioning its primary nature as a spire, window, or pew. This is what photographing means for Jodice. In this series it is concretised not only in the image of the pews mentioned, but also in glass, in its turn characterised by a triangular structure that obstructs a direct and explicit view from inside. Photographing is this capacity to see through a veil and obstacle. It is revelation and concealment together. Walter Guadagnini