This article was originally published on Domus 1087, February 2024.

In 1975, photographer David Hoffman, then in his 20s, visited the Barbican Estate. Like many Londoners of his generation, he was angered by the casual way in which established communities were being ripped up and their history erased in the pursuit of post-war urban renewal. He saw nothing to encourage him in the Barbican: “A massive, imposing structure seemingly dropped from the sky, the Barbican typified a wider uncaring and absolute power over our environment. Its great weight, the unassailable concreteness of it, the way that it resembled a walled city with whole areas locked and gated against outsiders – all these came together to say ‘You are no part of this’. It was the very opposite of welcoming; reeking of wealth, only navigable by those who knew the secrets of its confusing mazes and owned the right keys.”

Seeing it now, it’s difficult to believe that there was a time when the Barbican was unloved. In the very early days, when it was new and raw, people were reluctant to live here; flats were hard to let. I remember walking around on a Saturday afternoon in 1980 and seeing nobody. It was bleak. So too was the surrounding area. The entire City in those days became a ghost town at weekends.

In many ways, the Barbican represents 1950s thinking

The remarkable change that has taken place over the past 40 years is attributable to several factors, not least the opening of the Barbican Arts Centre in 1982. The effect was transformative. The Barbican ceased to be a dormitory development and at last became a cultural destination, as its creators had always envisaged. The Barbican Centre hosts an outstanding programme of classical and contemporary music concerts, theatre performances, film screenings and art exhibitions. As a Barbican resident, you can finish dinner in your apartment and be in your seat in the concert hall or the theatre in under five minutes.

Living here sometimes feels like a great privilege. Another factor is ownership. The Barbican Estate comprises 2,014 flats, maisonettes and houses, and is home to about 4,000 people. It was not conceived as “social housing” in the sense that it was never subsidised or rent controlled. The development was targeted at professional people working in the City, and let at market rates. That is until the right to buy was introduced under the Housing Act 1980. Today, virtually all the units are privately owned. With ownership, families put down roots and a settled community grew up. Two generations of Barbican babies now live here, some with families of their own. People come, they love it, and they stay.

Time is another factor. Over the years, the gardens and landscaping have matured, patterns of use have been established, and the regeneration of the neighbourhood has brought with it excellent restaurants, supermarkets and a host of other amenities. The City itself has also changed. With a variety of shops, restaurants and bars, it is a wonderfully vibrant place to live. Half a million people work in the City, but it has just 8,600 permanent residents. Immediately before the war, that figure was 16,000; by 1945 the number had halved and would continue to fall. The City sought to reverse that decline, the priority being to build new housing.

The first phase of that plan was the Golden Lane Estate (1951), widely regarded as a model for social housing. The Barbican, as the second phase, was to be significantly larger and more ambitious. The Barbican story begins at 12:15am on 25 August 1940, when the first German bomb fell on the City of London, close to St Giles, Cripplegate. It presaged the London Blitz, during which virtually every building in the Cripplegate ward would be destroyed or irreparably damaged.

In 1952, when the future of the Barbican was first discussed, barely 50 people still lived in the ward. There was no need for wholesale demolition, and no community to displace. The 14-hectare site was a wasteland.

The Barbican ceased to be a dormitory development and at last became a cultural destination, as its creators had always envisaged.

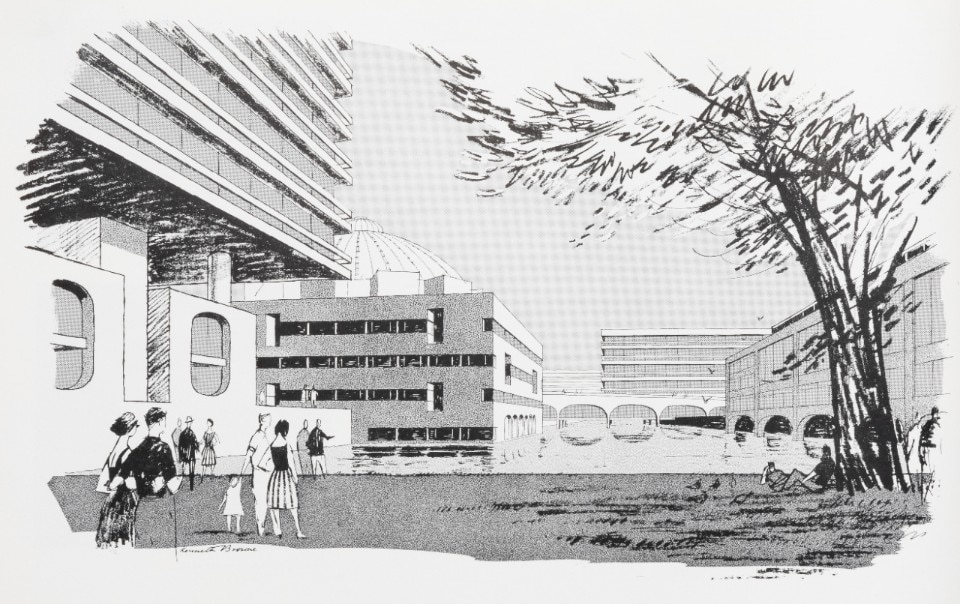

The Barbican Estate was designed by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, architects of the Golden Lane Estate, which adjoins it to the north. Like other architects of the period, they would have been familiar with the essays on townscape by Gordon Cullen and others, published in The Architectural Review. Cullen characterised townscape as “the art of relationship”. The “art” being to take all the elements that contribute to the urban experience and combine them in ways that release “drama”. When Cullen said that “a city is a dramatic event in the environment”, he might well have been referring to the Barbican. The Barbican is essentially a city within a city. It follows its own consistent planning logic, its chief characteristic being the separation of pedestrian and vehicular circulation. This is achieved through the use of “highwalks”, of varying scale and form, located two or three storeys above ground, with service roads and car parking confined to the lower levels. The scheme works beautifully at highwalk level, but is less successful where it confronts the existing street network.

A notable exception is the setting of Cromwell Tower at the corner of Silk Street. Looking at the perfectly judged little courtyard at the base of the tower, and then exploring the spatial variety of the highwalks, it is not too great a stretch to imagine the architects being inspired by Italian precedent. The tower houses, the piazzas and loggias, the formal vistas and tantalising views, the fortified walls and elevated vantage points are all redolent of the Italian hill town.

In fact, it is only when the architects fall back on Modernist tropes that the Barbican truly fails. The decking over of Beech Street being the most egregious example. Walking through this gloomy tunnel has to be one of the least rewarding urban experiences in the whole of London. Another weak point is the utilitarian treatment at street level on Moor Lane, where the architecture reverts to service entrances and car parks. Third, and most problematic for the visitor, is finding your way in or out, the routes generally being either unfathomable or counterintuitive.

In many ways, the Barbican represents 1950s thinking, particularly in environmental terms. Thermal insulation is primitive, windows are single glazed, and at an early stage the architects even considered the use of coal fires, before specifying electrical underfloor heating. The estate’s Garchey waste-disposal system, considered a marvel at the time, is identical to that used by Le Corbusier in the Unité d’Habitation, in Marseille, neither set of architects having anticipated the advent of domestic recycling.

In other respects the Barbican is visionary, embodying key elements of what we now regard as the sustainable city. Population density within the estate is high by London standards, at 285 people per hectare. This compares with 159 people per hectare in the most densely populated areas of Kensington, and 109 people per hectare in Central London as a whole. Public amenities are unrivalled, transport connections are excellent, with Tube and Elizabeth line stations to the east and west; and most people cycle or walk to work or to school. While the Barbican might not be a perfect model for the future city, almost everything about it is oriented in the right direction. Pioneering, and now also incredibly popular, it is unquestionably an enjoyable, rewarding and tranquil place in which to live.

Opening image: An image of the Barbican taken by David Hoffman in 1975 © David Hoffman PhotoLibrary

Outdoors: at the Milano Design Week, a new product by Nardi

With a patented system and durable, sustainable materials, Plano is Nardi's signature lounger designed by Raffaello Galiotto.