The entire globe, it seems, was transfixed by YouTube’s imagery of Notre-Dame’s super-close brush with death by inferno.

Even as Parisian firefighters staked their lives combatting the chimeric flames, and priests sped through the cathedral to rescue its 2000-year-old icons, a world-spanning ring of guardians began emerging with the collective vow to save the site from the brink of destruction.

Hundreds of scholars joining this constellation of Notre-Dame defenders – a computer engineer in Marseille, professors of medieval art and architecture in Pavia and Barcelona, Oxford and Kyoto, even a specialist on the physics of “explosions and fires” from Poitiers – pledged to give the French beacon a new incarnation that would radiate for countless generations into the future.

This transnational alliance, Scientifiques Notre-Dame, “was created spontaneously at an incredible speed,” says Livio De Luca, research director at France’s National Center for Scientific Research and one of the group’s founders.

But the ever-changing maze of border barricades and freeze-in-place lockdowns that has descended on the world since then threatened to halt any global quest to rebuild the sacred outpost.

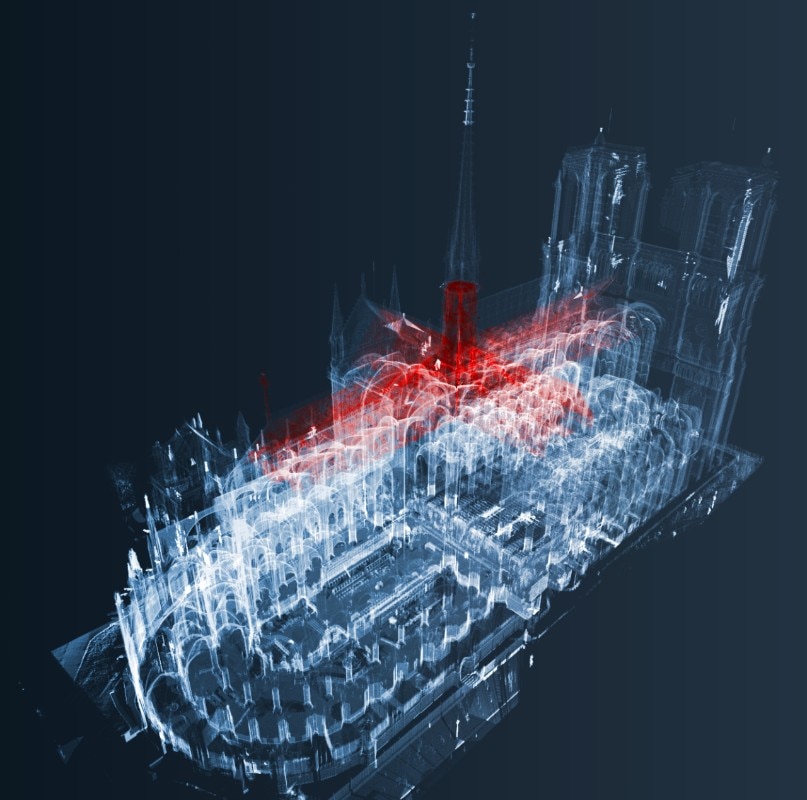

Yet De Luca, and his allies across French research labs and the Scientists of Notre-Dame, have tapped the revolutions in digital mapping, visualization software, virtual reality and cloud computing to create a fantastical “virtual twin” of Notre-Dame.

Donning VR goggles, scholars and sculptors, architects and coders can all meet and expand on this interactive simulation, reconstructing the cathedral virtually before each step is repeated in real-world Paris. Based in the cloud, this advanced avatar of Notre-Dame is a border-free zone open to digital designers and cyber-creatives across the planet, explains De Luca, who heads the coalition created with France’s Ministry of Culture to spearhead the cathedral’s virtual-to-physical resurrection.

While great swaths of life and culture – and even time itself – seem to have been freeze-framed of late, the Parisian cathedral, and the phalanx mapping out its phoenix-like rebirth, are speeding ahead into the future.

Across the upper tiers of the wounded structure, robotic photographers now zoom along a web of high wires, capturing images of the flame-lashed vaults set to be re-carved.

A squadron of miniature aircraft, led by Europe’s leading-edge Phantom octocopter, circles and surveys the site from above. Human surveyors armed with laser scanners are charting the structure as it is rebuilt, transforming their data into ethereal point clouds.

These laser-derived images are being combined with photo-based models to update the virtual double in real time, adds De Luca, who studied architecture at Italy’s Università Mediterranea di Reggio Calabria, and engineering at ParisTech, before earning an advanced HDR degree in computer science.

As scientists reconstruct the timber latticework and crushed vaults on the Notre-Dame sim, their advances will be replicated by artisans, trained in medieval carpentry or stone carving, now deployed across the 850-year-old outpost.

Plugged into the life-size virtual model, a scholar situated on the Mediterranean coast (or any other point on the planet) could visually walk a sculptor, stationed inside the actual cathedral while wearing a VR visor, through repairing a crushed carving. Via cameras positioned throughout the site and relaying images back to the virtual twin, this instructor can survey his apprentice’s success.

In myriad ways, De Luca is the perfect cyber-architect to lead Notre Dame’s tech-propelled rebirth. With his love of flying machines and soaring architecture, of timeless icons and radical experimentation in design, he bears a remarkable resemblance to Leonardo da Vinci – if the Renaissance artist-inventor were reborn in the era of The Matrix and augmented reality artworks that can be projected into the skies.

While great swaths of life and culture – and even time itself – seem to have been freeze-framed of late, the Parisian cathedral, and the phalanx mapping out its phoenix-like rebirth, are speeding ahead into the future.

De Luca has helped create some of the breakthrough technologies and software opening the way for an expanding metaverse of virtual architecture, artworks and galleries. To view this digital cosmos, he co-developed a wireless VR headset with an open-source design that can be freely downloaded – and replicated using a 3D printer – anywhere across the world.

As part of the movement to transform works of ancient architecture into digital maquettes, he teamed up with co-inventors at the French lab he heads, Models and Simulations for Architecture and Heritage, to convert a quadcopter into an aerial photographer. Equipped with a Raspberry Pi camera, the flying robot snapped images while orbiting part of a Greek temple, and beamed them to a nearby laptop.

At the forefront of European experiments in combining photogrammetry with advances in modeling software to sculpt digital dioramas, De Luca’s also been a torchbearer in enhancing photorealistic 3D models with sophisticated information systems, including semantic tags, archives and search engines.

These tech campaigns, he explains, are aimed at preserving cultural outposts that have been lashed by the tempests of time, and at reviving them. One key component in creating the Virtual Notre-Dame, he says, was the incredible spectrum of laser scans and point cloud imagery developed by Andrew Tallon, a Belgian-American scholar at Vassar College in New York who spent part of his childhood in Paris, entranced by the cathedral that seemed to animate the entire cosmopolis.

Tallon, who once contemplated becoming a Trappist monk, devoted a great portion of his life to immortalizing Notre-Dame with his high-precision laser surveys and panoramic photographs, says Vassar Professor Jon Chenette, his longtime friend. Tallon transmuted his scans into luminous models – composed of photons rather than paint pigments – that viewers can glide through like a true city of lights.

“The whole platform we are building today is only possible because Andrew Tallon spent so much time to scan the cathedral and create his mesmerizing point cloud images,” says De Luca. “The zero, zero coordinates of our platform are exactly the same zero, zero coordinates of Andrew Tallon’s very first laser scan of Notre-Dame.”

Although Tallon passed away just before the site’s own brush with tragedy, he would have been elated his laser scans are now playing a central role in its renaissance, says Chenette. But Tallon, who co-launched the Friends of Notre-Dame charity to help finance its restoration, “would have mourned the tragic fire that made his work an invaluable resource.”

De Luca says the cloned Notre-Dame actually encompasses a continuum of models depicting the site as it evolved through the ages – even its resurrected future. In that sense, he muses, “The digital twin resembles the tesseract in the film Interstellar, where you can see all of the temporal states at the same time.”

While Tallon’s laser surveys provided extraordinary imagery up until the eve of the fire, the VR mirror version would depend on incorporating scans right after the disaster.

Even as clouds of smoke still hovered over the site – and President Macron told the world it was France’s destiny to bring Notre-Dame back to life – the authorities issued an urgent appeal for the atelier Art Graphique & Patrimoine to conduct a new survey.

AGP is a European leader in digitally mapping masterworks of the ancients – like the endangered classical architecture of Palmyra and the soaring sculpted Greek goddess Nike – and transforming them into captivating VR artworks: its transmutation of the Winged Nike is now ensconced at the Louvre’s burgeoning virtual museum.

AGP rapidly dispatched a hyper-tech “SWAT team” - including laser surveyors and its specially trained drone pilot - despite the perils of navigating collapsed vaults, unstable walls and lead particles from the melted spire that contaminated the entire grounds.

“Safeguarding the cathedral was our overarching mission,” says Chiara Cristarella Orestano, an Italian archeologist at the studio. In just one day, AGP’s lasergrammetrists took scans from more than 300 positions across Notre-Dame.

These post-disaster images proved invaluable in assembling the site’s digital doppelgänger, says De Luca. Father Denis Dupont-Fauville, a Canon at Notre-Dame who holds a parallel post inside the Vatican’s papal court, says Tallon’s amazing sculpted-light models, combined with their pivotal role in reviving the imperiled beacon, might be interpreted as a sign of divine providence: “There were so many miracles in that story.”

Tallon presented his imagery as an eternal gift to the cathedral. Father Dupont-Fauville says the Parisian pompiers who faced off the flames to protect the church, and the priest who risked his life to rescue its most sacred relic, the Crown of Thorns, deserve the highest accolades. Yet he adds the scholars, surveyors, and artisans who are breathing new life into the site should also be hailed as heroes.

In a sign of the high-speed progress Notre-Dame’s constellation of guardians has made in reanimating the structure, the Crown of Thorns was slated to return to the outpost in the run-up to Easter of this year.

And by Easter of 2022, De Luca predicts, his cyber-alliance will release one version of the VR cathedral for admirers around the world to explore. The digital Notre-Dame is a test case, he says, a lighthouse of technological advances guiding the future toward preserving cultural icons virtually for an eternity. These coded clones can in turn be used to regenerate embattled architecture across the ages.

Opening image: Screen capture 1 of Virtual Notre Dame created by Livio De Luca’s Digital Data Group with France’s Ministry of Culture, based on laser scans by Andrew Tallon and the French outfit GEA. Credit © Violette Abergel, Livio De Luca - MAP - Vassar College - GEA - Life 3D - Chantier scientifique Notre-Dame de Paris Ministe re de la Culture - CNRS 2021