Cinema is not merely the seventh art. They say it’s also a form of comprehensive art, which encapsulates all the others. Among the rival disciplines of cinema there’s architecture. Often, buildings and spaces are not merely backdrops, but rather contribute to creating the meanings and hypertext of a movie. For example, it’s impossible to visualise Blade Runner and its sense of retro-futurist decadence far from its Modernist settings or the “Maya revival” of the Ennis House by Frank Lloyd Wright. And yet, it’s hard to come across films that literally could not exist without their architectural context, like Columbus, the first film by Kogonada, a Korean-American director and former critic and theorist.

Columbus, the film, exists, because Columbus exists – a small town in Indiana “the Athens of the prairies”, a place in the Midwest with a little over 40,000 inhabitants that would most likely have remained unknown to the world had a local—the businessman J. Irwin Miller—not established in the early 1950s the Cummins Foundation with the goal of promoting and subsidizing a series of architecture projects. The list of architects involved, from then to now, is staggering: along with the precursors Eliel and Eero Saarinen, there’s also I.M. Pei, Richard Meier, Robert Venturi, Harry Weese and Deborah Berke.

Unquestionably, one of Columbus’s most iconic landmarks is the Miller House, the private residence of J. Irwin Miller designed by Eero Saarinen with the collaboration of the landscape architect Dan Kiley and the interior designer Alexander Girard. Here, in its museumified beauty – the stuff of perfect archetypal ideas – the film opens and closes, in full circle. In the middle, we witness the encounter between Jin (a forty-year-old translator who left Seoul to run to the bedside of his father, an architecture professor, who had a stroke during a visit to the Miller House), and Casey, a young woman torn between assisting her mother, a former drug addict, and a potential university career on the East Coast. The film follows their pilgrimage among the buildings of Columbus while their chaotic lives, suspended in a sort of limbo, react to the logical, rational, philanthropic architecture, built with the goal of improving the practical conditions of life, with mutual influence, since the macrocosm comes to life when it is incarnated in the microcosm.

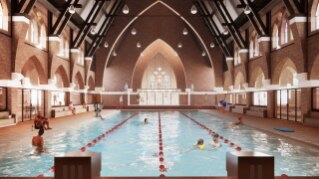

“He believes in modernism … Modernism with a soul. An alternative possibility”. Jin and Casey are visiting the North Christian Church by Eero Saarinen when Jin, who is starting to get to know his distant father through his passion for architecture, declares the professor’s lay, humanist credo. The Modernism of Columbus is a practical utopia for which the mental hospital by James Stewart Polshek appears like a bridge, in a literal and metaphorical sense, and the Irwin Union Bank, also by Eero Saarinen, was the first bank that didn’t want to look like a fort but rather give the impression of transparency through its all-glass façades. “More glass, transparency and light,” exclaims Casey while observing the enormous glass panels of the Republic Newspaper Building by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill: this could be the motto for the entire city.

If all the inhabitants of Columbus, “the Mecca of Modernism” – professors, tour guides or gardeners – seem intent on preserving cathedrals and tending to worshippers, in reality, keeping up appearances is a more problematic task, with existential fallout. If for some this is an edifying and thaumaturgic confrontation, in the film we see many lives gone adrift. And there are some enlightening dialogues regarding new technologies: Casey and her fellow librarian discuss the recent decline in attention spans and conclude that, maybe, it isn’t a decline in attention spans but rather in an interest for daily life, real life. Casey slams Jin for his addiction to smart phones: “smart phones, dumb humans”. So the human factor in Columbus is decisive on an emotional level. Humans are the animated part of the picture. Major architectural utopias and their spectacular creation would be inert if it were not for the environment that facilitates and informs an encounter between the stories of both protagonists, concretely improving their lives.

Attention and empathy for the minor stories of common people that become universal, archetypical narrations likens Kogonada to his professed maestro, the legendary Japanese filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu, and in particular his masterpiece Tokyo Story, which directly inspired Columbus. This is ideological fondness that cannot but become a quotation of formal aspects, thanks to which the ideology becomes manifest. Oftentimes, the camera is placed on ground level to evoke the “tatami shots” that were the Japanese master’s trademark while certain perspective shots could very well have appeared in Tokyo Story, if only the buildings were not Western. Besides, even the need for a particular architectural environment in a specific story stems from Ozu and his Japanese cinema of interiors. Kogonada is equally effective in adapting the style to the Modernist landscape as he builds a rigorously Cartesian space through plentiful central symmetries and horizontal track shots.

Columbus is truly a small (indie) yet big film because it doesn’t just display its theoretical and cinephile premises – integrating architecture with the narration and creating an American version of a “Ozu-esque” story – but, supported by excellent actors who are still mainly unknown to auteur movie-goers – assembles a specific account full of warmth and humanity. Kogonada’s minimalism is not aesthetic stylisation but a desire to strip things to the bone, to the root, to the heart. Modernism, precisely, but with a soul.

- Film title:

- Columbus

- Director:

- Kogonada

- Music by:

- Hammock

- Production company:

- Depth of Field, Nonetheless Productions, Superlative Films

- Year:

- 2017

Visual harmony and aesthetic

Now, more than ever, interior design is a balance of form and function, a dialogue between architecture, materials and finishes that transform and make the most of the space involved.