On 22 January, the Norman Foster Institute, an initiative of the Norman Foster Foundation, was inaugurated in Madrid with the presentation of its programme on Sustainable Cities, a master’s course combining fieldwork and academic research. In this month’s editorial, we publish Norman Foster’s inaugural speech, which, in addition to outlining the new school’s programme and structure, advocates the holistic approach to the design and management of cities that we believe should inform future generations of architects and civic leaders.

Why did we decide to establish an institute, and why is it being launched with a full-time one-year master’s course on cities and sustainability? These are natural questions to ask, especially since the Norman Foster Foundation, for the last six years, has been running an educational programme of workshops, public lectures and other initiatives. There are several answers. Firstly, I would say that it is because of the very success of the foundation’s educational programme. The institute evolves out of that programme, and it can benefit from the foundation’s worldwide network of experts on every issue that touches urbanisation and cities. We are very grateful to those experts and the institutions they represent for the generosity with which they offer us their time and wisdom. Cities are our future, and the statistics supporting this affirmation are overwhelming. Cities are tied to our wealth, growth, climate change, quality of life – the list goes on. But – and it’s a big but – to paraphrase Winston Churchill, we shape our cities, and they shape us. For cities to grow, evolve and respond to the challenges of change, those who lead and govern them must necessarily make decisions. Will those decisions be rational or emotional? Will they be based on data or fashion and prejudice? Fact or misinformation? Will the approach be bottom-up, involving the community, or a top-down imposition? Will the lessons of history be heeded?

The Norman Foster Institute is at the heart of these questions. This first course open to some 30 postgraduate scholars will be focused on training the civic leaders of the future and equipping them to lead with the strength of knowledge and experience. Other courses, still to come, may perhaps be shorter and more intensive, intended for those who are already shaping our environment by commissioning or procuring works of infrastructure and architecture. Such courses could be customised for a public authority or enterprise. This first course will be different from those offered by other educational institutions, predominantly universities. We are all grateful for universities and the wealth of talent that they generate. But academia also has its shortfalls. Aside from my own experience as a practising urbanist and architect, when I listen, as I do, to many young students and graduates, there is without question a disconnect between the academic world and the realities of life in the real world. This consideration led us to formulate a new proposition that seeks to marry the best of both of these worlds – academia and practice – into a one-year all-embracing course.

When I listen to many young students, there is a disconnect between the academic world and the realities of life in the real world. This consideration led us to formulate a new proposition that seeks to marry the best of both of these worlds.

To that end, we have created a new city laboratory in a separate building, a few minutes’ walk from the foundation’s headquarters. It is equipped with state-of-the-art digital equipment to create virtual twins of the selected cities. These can be used interactively as tools to explore design variations. They might be city-wide initiatives or proposals conceived for the scale of a neighbourhood or a public space. We combine these lab studies with seminars led by our network of experts in the classroom, and then the course moves on-site in one of three pilot cities to address real-life design challenges and engage with communities through city administrators. These challenges are the basis of projects that will be developed by the scholars and their mentors for presentations back in the pilot cities at the end of the year. These short-term projects would be tied into longterm sustainable goals.

The ability to communicate is linked to leadership, and these are skills that can be taught so they are also part of the course. In this first iteration, the cities are European: Athens, Bilbao and San Marino. However, the approach is universal, and the methods used can be applied to many different kinds of cities – formal and informal; Asian, African, American or Arabian. All are different but they share many of the same challenges.

Our provost Edgar Pieterse is the founding director of the African Centre for Cities at the University of Cape Town. Future courses will have a focus on Africa, especially given the estimate that by 2050 more than one in four people of the world’s population will be African and most of them living in African cities. As the United Nations advocate for cities across Europe, Asia and America, I have seen how cities can learn from each other. The foundation has incidentally been recognised as a UN Centre of Excellence, and this course will be linked to the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

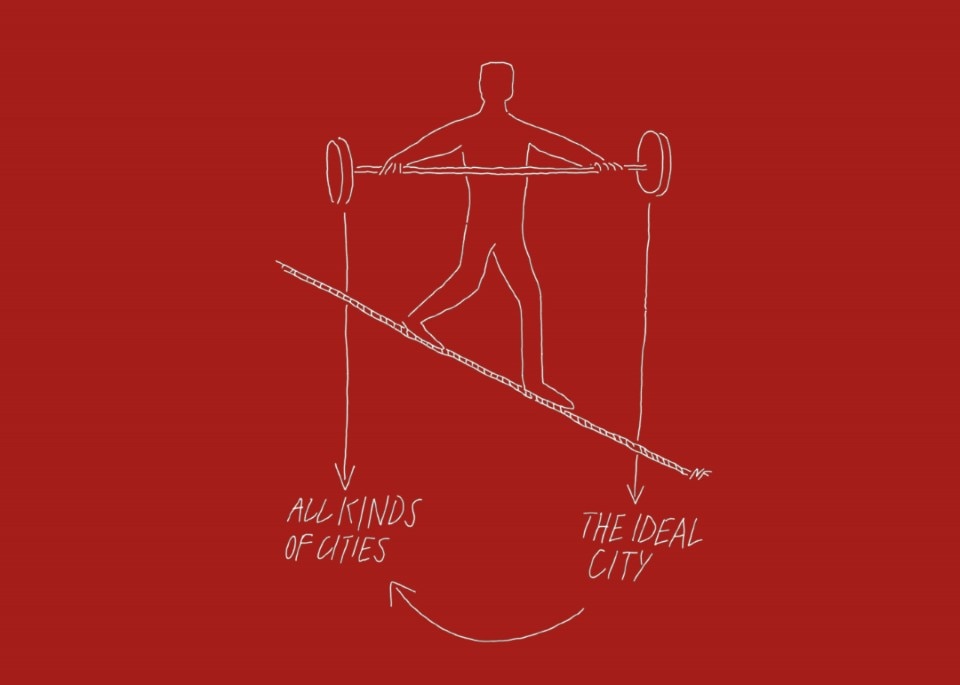

Another vital link to the course is MIT and its Media Lab led by Dava Newman, who has generously agreed to be the dean of the institute. The City Science group at the Media Lab is directed by Kent Larson, and it has pioneered the digital modelling of urban spaces. Kent and his team have worked with the foundation on projects and workshops, and this collaboration led seamlessly to Kent and I coming together as codirectors of this course. Kent also follows the evidencebased approach that I outlined earlier. As co-directors, we felt this course should do a balancing act between, on the one hand, embracing every kind of city and using all the tools and skills to improve the quality of life for their inhabitants, along with reducing their carbon footprints; and, on the other hand, promoting our ideal vision of the city of the future.

In reality, applying the principles behind our ideal city would inform any kind of city for the better in terms of shaping its future. So, what are the principles behind the utopian vision that we will be promoting? (Which, of course, we will invite the scholars and city administrators to challenge.) In summary, we would encourage the compact, high-density walkable city rather than the sprawling city which is solely or primarily dependent on cars. We would promote pedestrian-friendly neighbourhoods with zoning that encourages the proximity of spaces for living, working (including clean industries), education and leisure. We would advocate the importance of culture and heritage, especially in the historic cores that were the birthplaces of many cities. Finally, in this brief and incomplete summary, we would stress the importance of connectivity, ideally through high-quality public transport, as well as the promotion of nature, greenery and biodiversity throughout the metropolitan area, including even bigger spaces that could accommodate urban agriculture.

We would encourage the compact, high-density walkable city rather than the sprawling city which is solely or primarily dependent on cars.

These aspirations might all sound a little familiar. Many of the ingredients that I have noted already come together in those existing cities that top the polls in surveys of the most desirable places that tourists want to visit, and where people want to settle and bring up families. What is good for the quality of life also happens to be good for the planet. There is a vast difference in the energy consumption of a compact city versus a sprawling metropolis, quite aside from the devouring of precious countryside and nature. In all of this, Kent and I, along with the academic body and chairs, will be promoting the City Beautiful. If a city is a collection of many buildings, then it is bound together by the urban glue of infrastructure. Infrastructure comprises public spaces, boulevards, streets, squares, plazas, bridges, terminals and metros. That infrastructure determines the identity, the DNA of a city.

It can and should be beautiful. History has many lessons for us to learn from. The history of activism is also important. Jane Jacobs’ plea in the 1960s to respect the complexity and spontaneity of cities is also not lost on us and is entirely compatible with the systematic design methods that are at the core of this course. The 1960s also brought forth those activists who combined the rhetoric of words with sketches and photographs to protest the civic vandalism of the period that was destroying much of traditional urban beauty. They also promoted the qualities of traditional townscaping principles from the past – of surprise and enclosure. These messages from generations past are even more important and timely today. For me, those roots go back to my student years in Manchester and at Yale. There is another student link here today.

In the 1980s I became aware of a new way of looking at the design of cities and urban spaces. This approach combined observation with computer-aided design to quantify connectivity, particularly pedestrian movement. It was pioneered by Professor Bill Hillier at The Bartlett School of University College London. At that time, I was heading the development of a master plan for the regeneration of King’s Cross in London that would change a wasteland of railway sidings into a new park, neighbourhood and European train hub. I used it as an opportunity to pull Hillier and his team out of academia and for him to create a consultancy that he called Space Syntax. One of his students at that time was Tim Stonor, and he is to be commended for carrying on the good work of Space Syntax as well as continuing to help the foundation and now its institute.

There are so many sponsors and supporters who have helped to make this new institute possible, and like the institute and its first intake of scholars, they are truly global. But our base is here in Madrid, so it is a cause for celebration that the Autonomous University of Madrid has come together with us in a partnership in which they will formally recognise this first course as a master’s degree. Finally, when I was asked by the Secretary-General of the United Nations to address the General Assembly on the importance of master planning, I was reminded of the words of Daniel Burnham talking about his Plan of Chicago in 1909. His words resonate beyond cities and planning:

- Make no little plans;

- Make big plans;

- A noble logical diagram will never die;

- Let your watchword be order and your beacon be beauty.

Opening image: Sketch by Norman Foster illustrating the need to apply the principles of the ideal city to inform all types of cities.