In a former cafe on a narrow market street in South London, a small workshop called Assemble & Join, centred on a large state- of-the-art cnc milling machine, hosts lessons in the practical potential of digital manufacturing for the local community.

A high-street role for the maker movement seems imminent. “High streets are becoming more about civic space and delivering beyond pure consumption,” says Joni Steiner, an architect at 00:/, the team behind a new website and host ecosystem for a “freemium” model of digital manufacturing, OpenDesk.

“Soon it’ll be like, ‘I’ll get a coffee and print that thing.’” Where ikea has succeeded in flattening the relationship between the user and design objects, lo-fi manufacturing and DIY, 00:/ see an opportunity to bring industry and production back to the city, and users back to design.

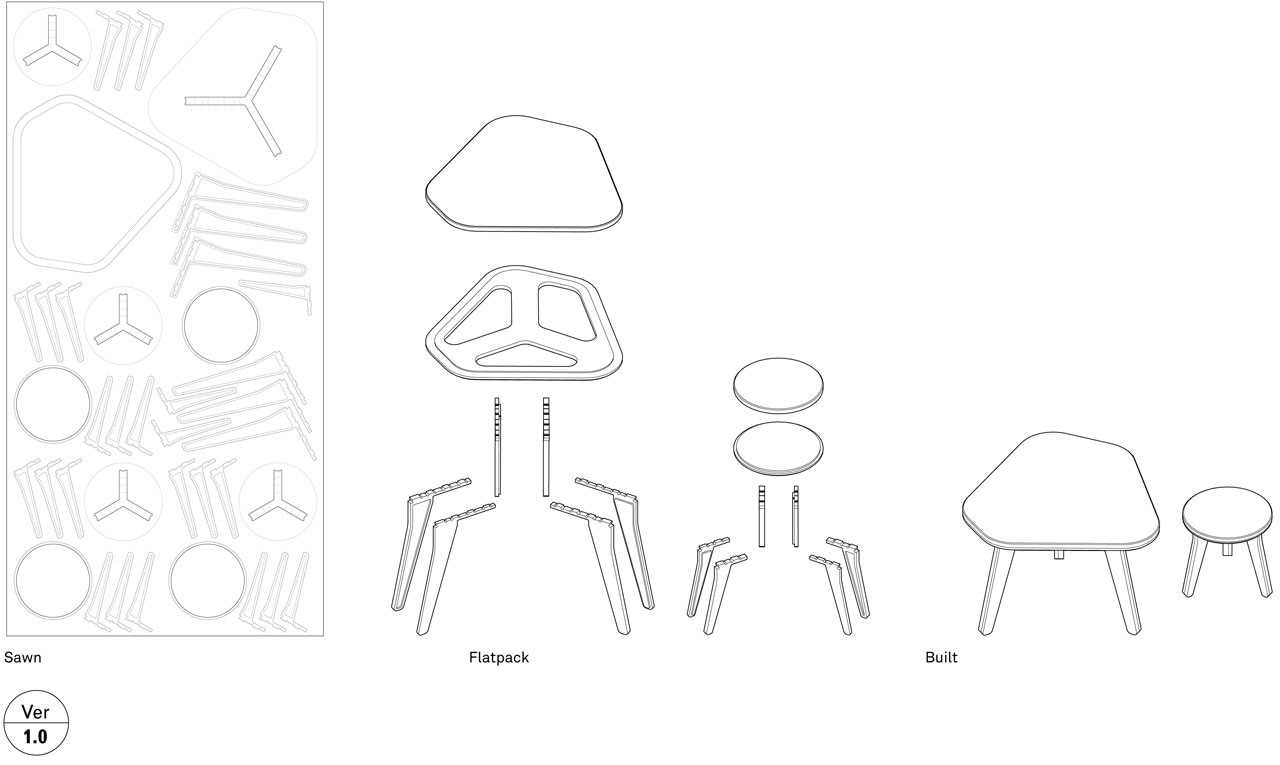

FabHub and OpenDesk are online infrastructures designed by 00:/ to nurture and utilise such networks of professional and hobby makers. Both a free open-source furniture showroom and an experiment in the possibilities of distributed manufacturing, the website connects users to simple free design templates and the “factory”, providing details and maps as well as reviews and feedback systems. And it’s designed to make money

Critically, OpenDesk is a commercial proposition. Accordingly designs can also be purchased, either as finished items or under a re-seller license, where makers can reproduce the designs in their locality and sell them on for their own profit. OpenDesk, meanwhile, receives a modest design fee and the designer receives a royalty. Nick Ierodiaconou explains the business model as similar to freemium software. “All OpenDesk furniture designs are provided freely under a creative commons license for anybody to make themselves,” he explains. “

However, OpenDesk is also connected to a growing network of local makers, who provide quotes for fabricating, finishing and delivering products. We see this as a new model for making, where shareable digital designs, the Web and the growing capacity for digital fabrication lead to more peer-to-peer production in a hyper-local supply chain.” The structure of both websites is considered enough to establish a royalty system for the designer, along with reviews and ratings for manufacturers in a kind of internal auditing system.

“It’s a bit like the eBay reputational model, where makers comment on how well a piece was designed—how makeable

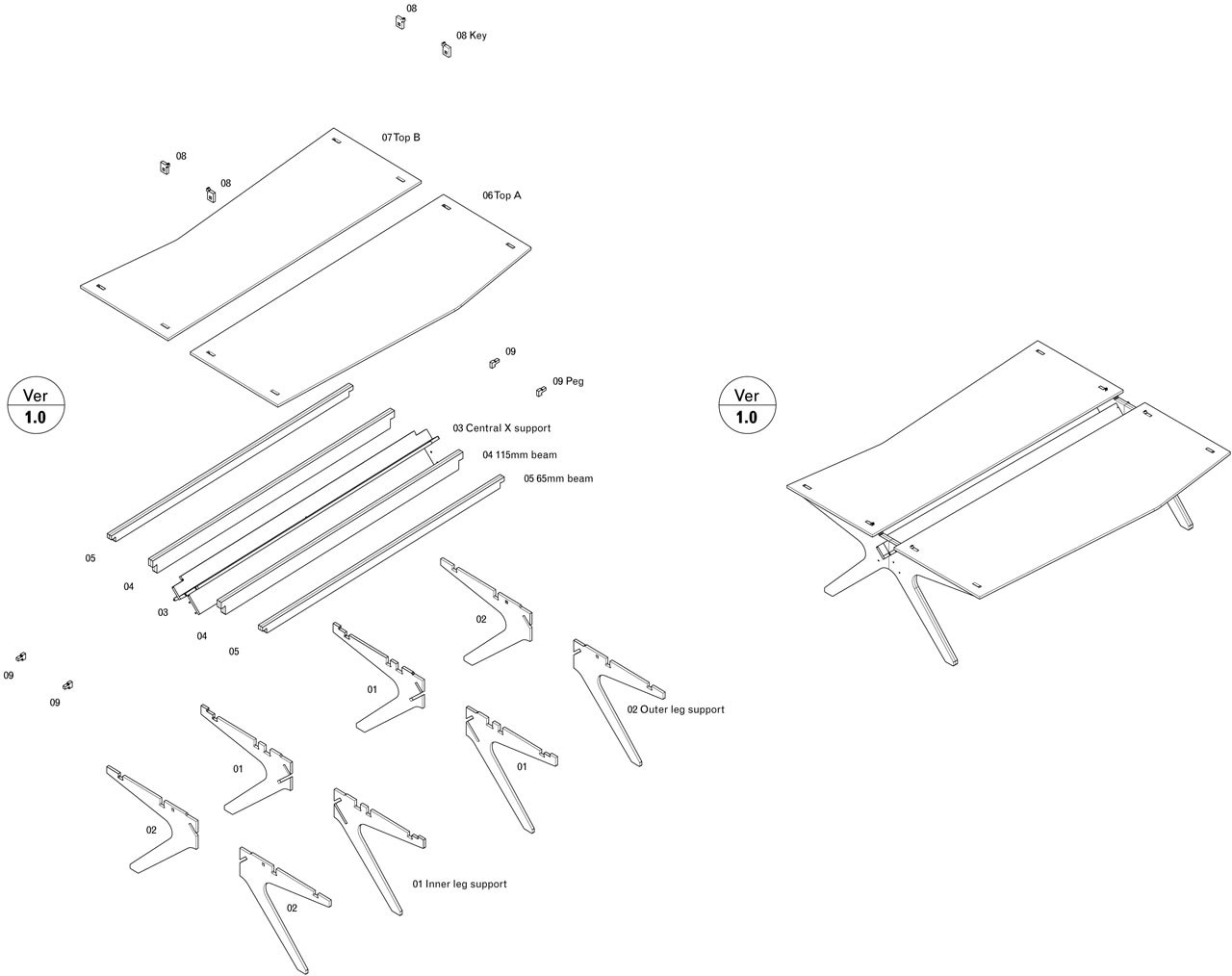

it was—and how well they made it from a consumer point of view,” says Steiner. “It’s establishing a different relationship.” OpenDesk started with a commission for an open-source desk for a client in 2011 whose offices were in London and New York. 00:/ proposed a bespoke desk that was not only shareable across the two offices, but also easily reproducible, as they were anticipating rapid growth in both cities.

00:/ continued the furniture project, producing their own office desks for their home at Hub Westminster, and the conversation evolved into their open-source house project, WikiHouse.

“There’s something called the ikea effect,” says Steiner, citing research by the Harvard Business School that defines an increase in the perception of value for those whose labour and physical effort goes into a task. “You actually get a lot out of building and making something yourself. You’re more attached to it and you assign it with a larger economic value.” One of the most common critiques of open-source design and digital manufacturing is its aesthetic limitations. And no matter how elegant the design, a transformation in interest for a home or office entirely made of digitally-cut 18-millimetre ply seems doubtful. OpenDesk and FabHub have identified similar issues among online shopping competitors, and are quickly expanding into plastics and other materials to augment the collection.

The next stage for 00:/ is to move towards consumer products designed by others, for all sorts of digital fabrication, particularly focused on a relationship between emerging designers and new types of manufacturing. This development will provide access to a network of makers, allowing a product to be made near the buyer, and enabling designers to sell products directly to the market. It is certainly in the community’s interests to continue expanding its range and embrace the thousands of designer-makers around the world, followed by the important step of a far-reaching editing process. After that, it’s over to the next urban revolution—high- street micro-manufacturers—to make it happen. Beatrice Galilee (@_Beatrice) Architecture and design curator and writer