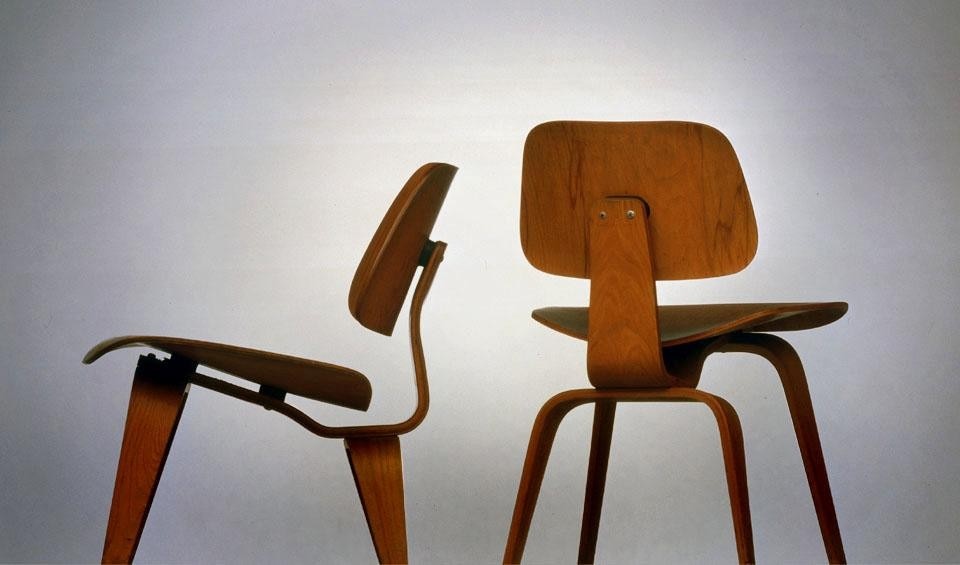

More than his work, including the famous plywood and metal chair, what we find interesting in Eames is his mental attitude towards design. His way of perceiving the architect's work is particularly topical as it is quite common among the entire generation of young professionals today.

It is well-known that the language of modern architecture was formed by three distinct fields - stylistic freedom, technical engineering and the recognition of the fundamental human value of architecture. Yet these are the three starting points from which architects began building their reasoning, each according to his own natural inclinations. The predominant position in Charles Eames' inspiration is occupied by modern technique: an unknown, so rich and capable of superior solutions, so improved and so complex as to seem almost broken down into many specific components.

One example is the degree of perfection found in some industries such as shipbuilding, automobile production, aviation; and even in apparently less related sectors such as plastics or surgical equipment in which many obstacles have been overcome and resolved, from the absolute exploitation of space to lightness, from mass production to the insurance of every comfort. And while their labor is constant and continuous, their equipment relentlessly upgraded, the construction industry is immobile in the security of having solved all of its problems for centuries.

To place Eames' work in the right light and to understand its energy and the stunning novelty of his achievements, one needs to remember that he comes to architecture from "industrial design."

At the end of the conflict, however, production technology was developed, and now, after the resounding success of the first set of series furniture presented in 1946 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Evans Products Company is involved, having entrusted the furniture's distribution to Herman Miller.

This renewal finds its reasons, thanks to the imagination of the artist, in new production processes and in the full use of modern technology. Eames is so aware of this, as evidenced in his controversial statements, as to reverse the process of composition and to think of technology as architecture's true grande dame.

I am sure that if I asked him, Eames would propose the industries' most advanced catalogs as the true texts for teaching architecture. Of course, if on theoretical grounds this is unsustainable, even this certainty gives Eames - who believes in it - great vitality and a kind of thirst for research that knows no limits to its investigation.